I love reading books about WWII. The Shelburne Escape Line is a true tale of members of the French Underground’s heroic efforts to rescue Allied airmen shot down over enemy territory. Author Réanne Hemingway-Douglas interviewed several pilots who gave their thrilling account of escape, evasion, and rescue. Here’s Ken Sorgenfrei’s story.

First Lieutenant Ken “Sorgy” Sorgenfrei unpinned his military wings and gave them to a farmer’s wife before escaping into the mountains near Grenoble, France. It was World War II and USAAF pilot Sorgenfrei had just completed what was supposed to have been his last bombing mission before returning home. After successfully releasing the bombs over the Munich railyards, Sorgenfrei’s plane was struck by German anti-aircraft fire, blowing out the nose turret, two of the plane’s four engines, and the electrical circuits, cutting off the oxygen supply.

First Lieutenant Ken “Sorgy” Sorgenfrei unpinned his military wings and gave them to a farmer’s wife before escaping into the mountains near Grenoble, France. It was World War II and USAAF pilot Sorgenfrei had just completed what was supposed to have been his last bombing mission before returning home. After successfully releasing the bombs over the Munich railyards, Sorgenfrei’s plane was struck by German anti-aircraft fire, blowing out the nose turret, two of the plane’s four engines, and the electrical circuits, cutting off the oxygen supply.

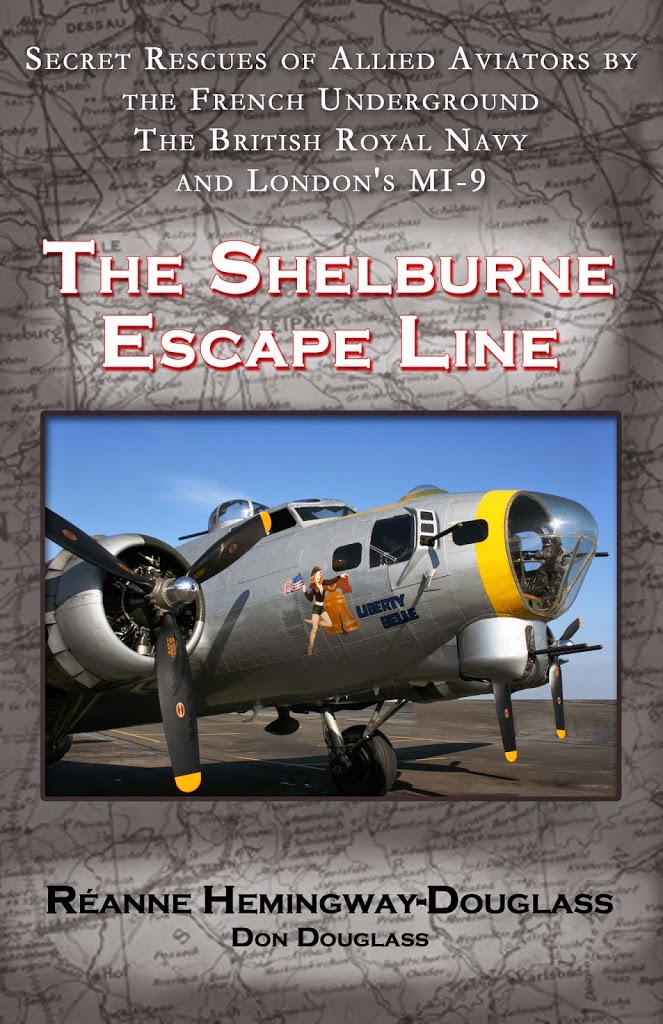

Sorgenfrei and his crew of nine were a tightly-knit squadron who had trained together as USAAF pilots and were considered one of the best crews to fly the new B-24 bombers. Determined to fly out of enemy territory and into Switzerland, Sorgenfrei told his crew to lighten the plane’s load. They released the remainder of the bombs and dumped the machine guns, ammunition and any equipment they could spare. An hour later, one of the two functioning engines died and Sorgenfrei ordered his crew to bail out. He was the last to parachute and landed unconscious in a valley near Grenoble. He and his entire crew were rescued by the local villagers. The farmer’s wife to whom Sorgenfrei would eventually give his military wings was the one who found him and brought him to her home.

With the Germans searching the area for survivors, local Resistance members took Sorgenfrei, suffering from a badly sprained ankle and a concussion, and his crew to higher points in the mountains. They traveled up into the Alps and were eventually turned over to members of the Resistance de l’Oisans, then taken to an abandoned ski resort where the crew began working in an Allied field-hospital for the wounded.

Two weeks later, the Germans learned of the hospital’s location. The airmen evacuated everyone and moved higher into the mountains. When the Germans began to close in, the airmen hid the severely wounded in a rock cliff.

On August 22, a month after Sorgenfrei and his crew crash-landed, Allied forces liberated Grenoble. When the airmen returned from the mountain a week later, the villagers of Grenoble welcomed them as heroes. The hidden wounded were rescued. The entire hospital staff: two doctors, half-dozen severely wounded patients, one of the doctor’s wives, the fiancée of one of the wounded, and Sorgenfrei and crew had survived the ordeal.

In 1985, Sorgenfrei and some of the airmen returned to Grenoble to retrace their escape route from the crash site in the valley up into the mountains. At the end of their journey, the villagers who rescued them in 1944 gave them another hero’s welcome. An elderly woman walked up to Sorgenfrei. He was shocked to see her wearing his military wings. It was the farmer’s wife who had saved him on that fateful day.

To read more stories about heroic pilots who survived after being shot down over German-occupied France in WWII and about the French Resistance who rescued them, read Réanne Hemingway-Douglass’s The Shelburne Escape Line.